STORY / KOKO NTUEN

PHOTOS/ JASON RODGERS

STYLING / TIFFANI WIILIAMS

GROOMING / HECTOR DE JESUS

ART DIRECTOR / PHIL GOMEZ

SHOT @ EDEN STUDIO

You don’t go into the studio with Busta Rhymes and come out the same person. Cells shift. Tears flow. Lessons land. Knowledge forms. Joy erupts. Love—real love, ancestral, cosmic, mischievous—gets transmitted straight to your bloodstream through pure resonance.

I show up to Quad Studios, a notorious hit-making lair hidden in the neon chaos of Times Square. It’s the middle of the night. I’ve got an entourage, a handle of Grey Goose, and a half-workshopped rap I wrote in ode to Mr. Rhymes scribbled on a Soho House napkin.

Quad is a place with lore. A studio that has created hip-hop history and, at times, rewritten it. This is the same building where Tupac survived a shooting in ’94, the lobby forever haunted by that moment, the walls humming with the kind of canon only danger and genius can co-create.

It’s an era where Busta Rhymes’ mythology was sharpened like a samurai’s sword, razor-edged, calculated, and with divine messaging. Thousands of songs later, hundreds of collaborations, countless verses, and a style that bent the rap genre’s spine into new shapes, he wasn’t exaggerating when he proclaimed he’s got Rhymes Galore. His arsenal of musical mayhem has topped the charts and scored countless pop culture moments and generational shifts. Inside the studio, he’s a maestro, commanding elements the way a preacher knows scripture—with ritual, rhythm, and the sacred geometry of sound.

Busta Rhymes doesn’t arrive. He detonates.

The day before, I’m outside on a Chelsea street corner with his publicist as we await Busta’s arrival to set. It’s like a tactical military operation. We are summoned out, a silent Maybach glides to the curb. A bodyguard emerges from the armored car, sternly scanning the block. A discreet signal happens, and an assistant opens the door. For a split second, it feels like a freeze-frame from a gangsta movie: THE Busta Rhymes stepping out, crisp denim set and sparkling accents glisten under the streetlights, white sneakers so pristine they look like they haven’t met oxygen yet, and a presence that feels like a bomb.

He’s on a call—loud, booming, electric— his voice is too big for his body, and he looks like he could be a retired linebacker. He doesn’t stop walking, straight from the car to an open door, which is being held open by another assistant; we turn around and follow.

“This is Koko, with LADYGUNN,” the publicist says.

“I’M ON THE PHONE,” he snaps, then looks at me. “Hi, how are you doing, sweetheart?”

As the elevator doors close, the air tenses. His team stands straighter, and everyone looks forward. I try to make eye contact, and then when I do, I try not to giggle. It’s a nervous habit. Busta Rhymes is a storm entering a room, and the atmosphere adjusts itself around him.

There’s no question that showmanship is less of a calling and more of a birthright for the artist. A seasoned, trained performance guides his movements and makes small gestures and subtle expressions more enchanting than they should be. Akin to a smiling baby, he elicits the coos and caws of spectators on the sidelines, “OMG I LOVE THAT,” “SO CUTE I’M DYING.” We all lament.

His Mask-esque, cartoon-come-alive charm glows under a camera flash. He’s really interesting to look at, which has contributed to his status as a pop culture juggernaut and one of the most recognizable characters and personalities in the world.

He discusses fame with surprising softness.

The young Busta wanted it—needed it—to provide for his child.

But the older Busta?

“Fame is expensive. Privacy is priceless.” He reflects.”Security, drivers, assistants, overhead, constant eyes. A production every day. No space to handle personal calls or sacred family issues without ears watching.”

Meanwhile, the wealthiest men in the world roam unnoticed. “They got all the money. They control everything. But we don’t know what they look like.”

Busta found success relatively early, signing his first record deal at 17, but demands came quickly after.

“I had my first child at 21 while I was still living with my mother. So I wasn’t a man yet, but as a father I was forced to learn how to become a man quick.”

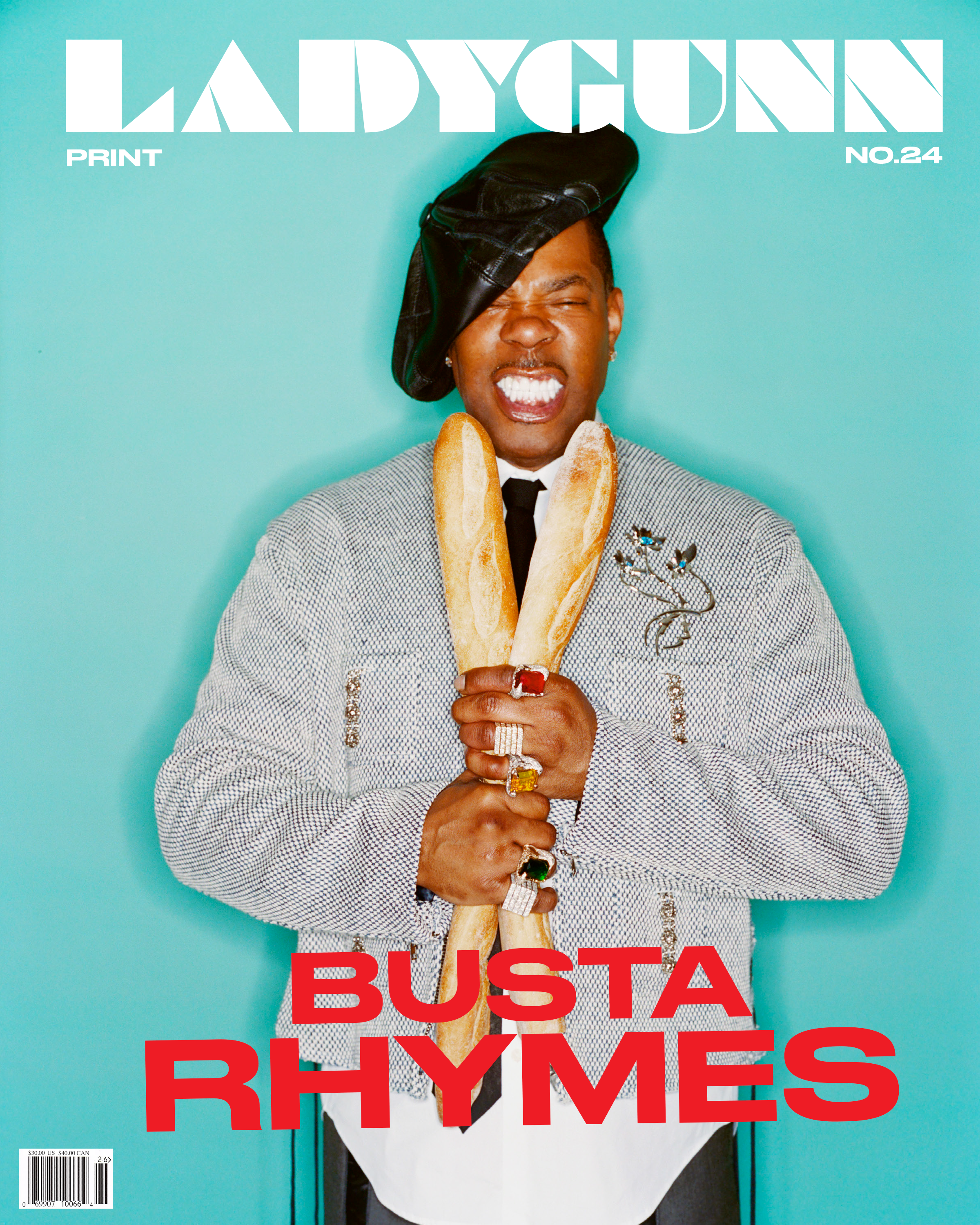

Shirt: Theory. Jacket: EZR. Pin: Collina Strada. Pants: Koddy Phillips.

At the time, he was in his first musical act, Leaders of the New School. A high-energy quartet that was a manifesto to Black boyhood in all its humor, frustration, and electricity. Their playful, intricate rhymes, call-and-response cadence, and undeniable stage presence was a fresh injection to rap. Under Public Enemy’s mentorship, the group became a pivotal force in pushing hip-hop beyond its old-school roots, spotlighting youthful rebellion and Afrocentric consciousness as the genre evolved into something bigger and more self-aware.

“Being smart was super cool back then,” Busta says, describing the knowledge-of-self culture he grew up in. He was born to hard-working Jamaican immigrants and raised as a Seventh-day Adventist in New York. He came of age inside a first-generation, international technicolor diaspora, a childhood that defined him long before music did.

The streets were alive: “You’d see groups of Zulu Nation members…copies of How to Eat to Live by the Honorable Elijah Muhammad. You’d see the 5% Nation of Gods and Earths. Ansar Muslims selling chew sticks, Dr. York books, and oils. Africans selling kente cloth and incense. The Nation of Islam selling newspapers and bean pies. And a lot of Rastas sharing the ideas and philosophies of Haile Selassie I—the Conquering Lion of Judah—and Rasta culture. It was all around us,” he says. “Respect was mandatory.”

Leaders of the New School didn’t talk about nefarious street dealings, not because they didn’t live it, but because the hustlers around them didn’t condone it.

“They really wasn’t allowing us to talk about the hustler shit that they was doing or that we was doing. So we kind of stayed away from talking any of that shit because it just wasn’t green lit by the homies that we was moving around with.” Busta remembers.

In turn, a new genre of music was created that highlighted the angsty curiosity they were harnessing outside the classroom. Busta remembers clashing with teachers over the sanitized curriculum. Black history month reruns, Columbus myths, the same narratives repeated with no truth.

Jacket: s.k. Manor hill Top: Pleasures Pants: Kill off Season Shoes: Balenciaga

“We was wondering why y’all ain’t teaching us the shit that we’re learning outside of school at the school!? That shit created a lot of conflict because they classified the shit that we was doing as disruptive because we was disruptive about what we knew.

So, we was always on some ‘Teachers get the fuck out of here’, shit. Obviously, the Board of Ed has its agenda, but we were still on some ‘Fuck all of that shit’. That ended up leading to us having problems with school.”

That disruption eventually led to conflict, suspensions, and then to Busta dropping out altogether. But the hunger for knowledge, the questioning, the refusal to accept a script written for him, that part stayed, and with it new temptations.

“By the time I was 12, I caught two drug charges. That’s why my mother moved me from Brooklyn to Long Island, and that’s how I met Leaders of The New School. So anything to keep me from being in the street, my mother was with it. My moms would do anything to keep me in the studio. She would cook at home and bring it to the studio for all of us. She would sign my deals whenever those opportunities came. She was just always pushing me not to go back to the street.”

Busta was locked into New York’s raw musical renaissance in the early ’90s. His voice woven into the era’s most unmistakable textures and a central part of the hip-hop ecosystem. His 1991 verse on A Tribe Called Quest’s “Scenario” cemented a new future for the artist, positioning him as a voice that bent tempo, tone, and attention in his favor. By the time he appeared on “Flavor in Ya Ear (Remix),” he had carved out a foundation strong enough to shift the culture. Standing shoulder to shoulder with Biggie, LL Cool J, and Craig Mack, he was an infectious wild card who always stole every scene. He became the go-to hook, verse, or energy generator for anyone trying to elevate a record.

Other opportunities followed, and Busta’s face became part of the golden age of black cinema and celebrity. He shone in notable film roles like 1993’s Strapped and as a co-star in the cult classic Higher Learning (1995) by John Singleton. It was a defining moment in Hollywood; young, gifted, black, and impossible to ignore.

He was as ferocious as he was effervescent—like a Kehinde Wiley painting come to life. Busta’s style and aura were distinctly Afro-futurist: regal, kinetic, grounded in history while reaching forward. He carries himself with a deep, uncompromising sense of respect, the kind of man who would instinctively call your mother ma’am. That grounding wasn’t accidental. It was learned early, enforced at home, and carried everywhere. For Busta Rhymes, it isn’t about dominance or fear—it’s about clarity, boundaries, and honoring where you come from.

“As you get older, you understand how to give the same respect you want in return,” he says. “Anybody deserves that.”

That ethos shapes how he moves through music even at its most volatile states. During hip-hop’s most combustible era, Busta saw himself less as a participant in conflict and more as a stabilizing force. “If you cool with everybody, you don’t pick a side,” he says. “You try to neutralize it. You try to calm it down. You try to squash it.”

This was a generation that wasn’t supposed to exist: young, strong black men with financial freedom, fashion influence, knowledge of self, political awareness, access to information, and a new technology called hip-hop that could spread those ideas at the speed of sound.

Drugs were infiltrated into the streets, prisons filled faster than schools, and young men of color were criminalized faster than they could be understood. Rap, too, became a tool for division—especially across coasts and gang lines. Busta remembers that time vividly. Was it a scary time?

“I wasn’t scared of nothing because it wasn’t nothing to be scared of. I didn’t like it. It wasn’t necessary, and I think that it should have never got to that place. It really wasn’t never an East Coast, West Coast thing until the media turned it into that. All of us had a strong friendship.”

He was never interested in playing the tough guy for performance’s sake. “The goal was always to leave the streets once you got on,” he explains. “Being in music was about bringing feel-good energy, not fucking up your opportunity.”

He’s clear that the war was never just external. It wasn’t only industry politics, contracts, or labels reshaping the rules mid-game. It was mental. Emotional. Spiritual. The slow erosion that comes from being watched, commodified, misunderstood, and still expected to perform at the highest level without breaking.

“You speak things into existence,” he says. “I call my children what I want them to become. You tell a child they’re a king, a young god—those impressions last. That becomes a way of living. These are things that my children was born into. Busta Rhymes has six children: “I named them attributes because your name should be a name that is attributed to the way you live.”

To Busta, understanding is the absence of confusion. The clarity that lets you see yourself clearly enough to recognize the power in everyone else.

“The word minority is the biggest fuckery in existence. The biggest misconception in existence. And I’m never going to play with the power of the people. That’s amongst me. Because you don’t understand or realize the true value of that individual—especially if you don’t even understand the true value of you—let alone the true value of how we have to coexist for all of us to be powerful. I ain’t powerful without this motherfucker. This motherfucker ain’t powerful without you, queen. You ain’t powerful without maybe even just him alone. And then we ain’t powerful without them two. Everybody got some different important shit to bring that the next person can’t, because they weren’t even designed to create what they create. But we ain’t designed to create what that motherfucker create neither, because he might come with a fucking mineral that just don’t exist outside of the production of his people.”

Busta directs more than he listens. When he does speak, it’s ordained—no compromise. Sometimes it’s hard to tell where the speakers end, and his voice begins. When he’s fully in the music, it feels as if the whole room is coming out of him. It’s supernatural.

Despite the bombastic sounds, the beats reverberating against the walls, the space itself is sanctified and healing: charcoal is burning incense in brass urns, endless wine is poured into cups, sounds are blurring between moments, emotions capture us all at different times, and sometimes together.

“This is sacred,” he says, gesturing around the room. “You don’t just come in here bullshittin’.

It’s completely spiritual. When I’m talking, and I’m saying what I’m saying on these songs, it’s coming from a belief system. And it’s not just coming from a place of believing in something that I don’t know about or that I’m never going to see or touch. It’s like we was always taught that God is in the sky and it’s this mystery that you ain’t going to see. But there’s so much proof of who and what the true and living God is, you have to go and dig deep to research to get to that truth.”

He’s not interested in chasing relevance. He’s interested in preservation—of voice, of spirit, of truth that we all exist as fractals of greatness.

Sitting across from him, you understand his strength doesn’t come from volume alone. It comes from surviving systems designed to exhaust him and still choosing joy, humor, and generosity.

2026 becomes a major anniversary year across Busta Rhymes’ catalog, celebrating three and a half decades of uninterrupted cultural presence — not nostalgia tours, not legacy branding, but active authorship. Thirty-five years after A Future Without a Past… and thirty years after The Coming announced his solo arrival with “Woo Hah!! Got You All in Check,” Busta remains active, not archival. Twenty-five years ago, Genesis signaled his evolution into the new millennium, twenty years since The Big Bang debuted at No. 1, and just six years removed from Extinction Level Event 2. These milestones don’t read like nostalgia; they read like continuity. Busta isn’t celebrating a legacy, he’s still writing it.

There’s no separation between the music and the message. He mouths the tracks like a prayer. He laughs when he wants to, deep, sudden, like no one is watching, it’s as contagious as it is purifying. It’s past 3 AM when we start to gather our things. He’s posted up in a swivel chair, eating a Jamaican patty, in the studio with no sign of lowering the volume or stopping the ritual.

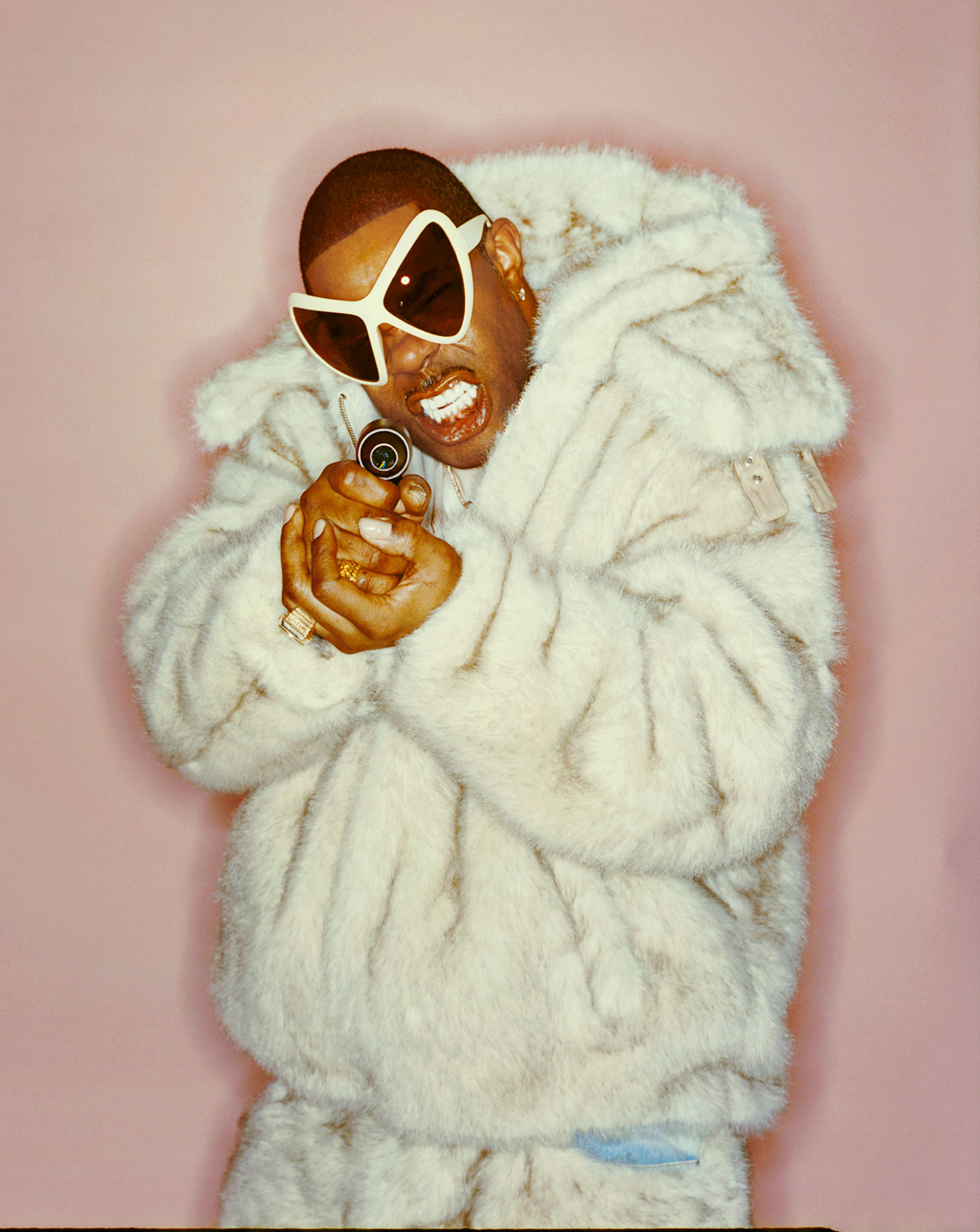

Jacket & pants: Kidsuper. Top: Sk Mannor. Sunglasses: Collina Strada.

Shirt: Theory. Jacket: EZR. Pin: Collina Strada. Pants; Koddy Phillips.

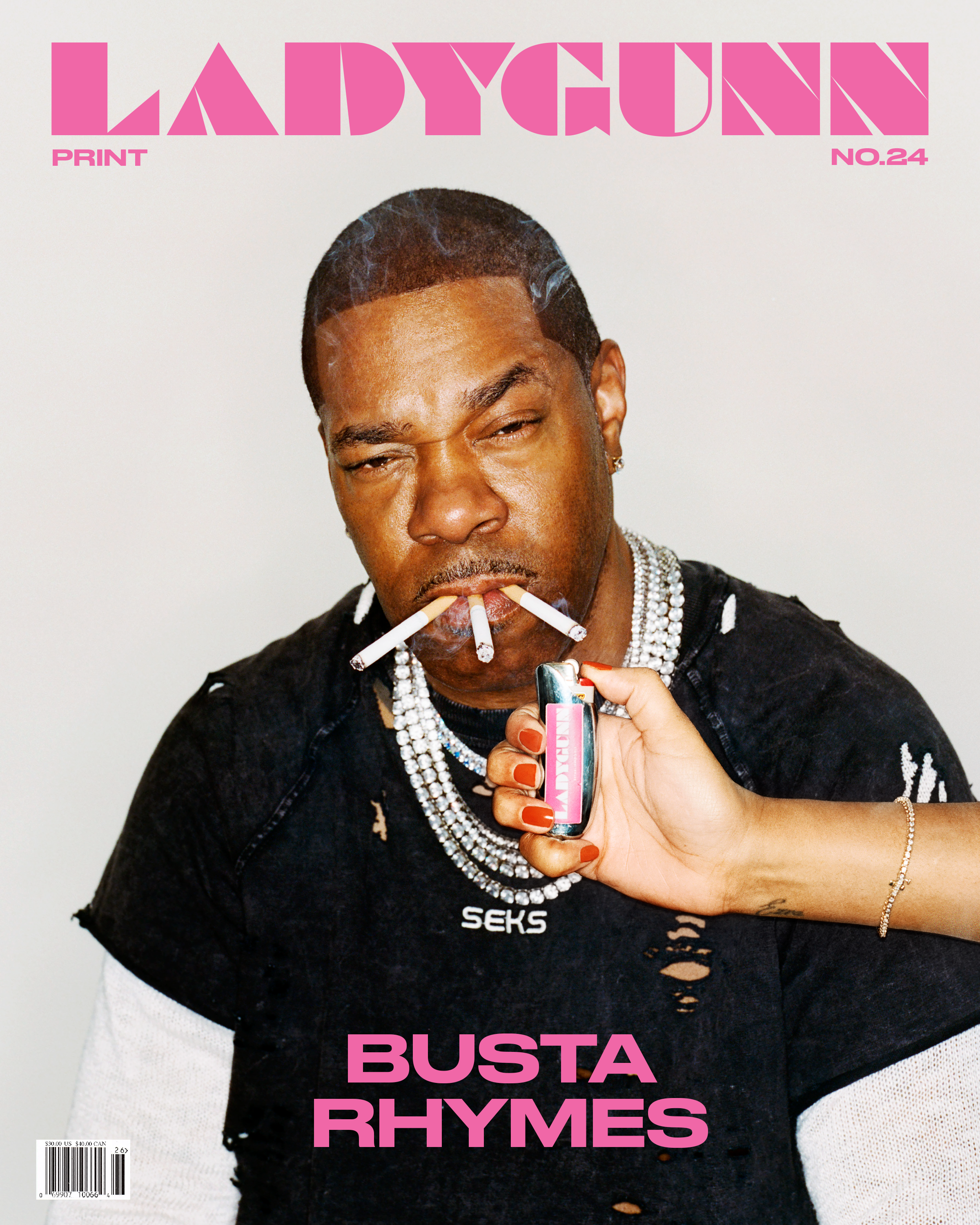

Top & bottom: Seks. Sunglasses: Rick Owens.

CONNECT WITH BUSTA: