Story / Joann Zhang

Photos / Carianne Older

Styling / Phil Gomez

MUA / Francie Tomalonis

Hair / Sean Fears with @opusbeauty

Location / 1 Hotel West Hollywood

Special thanks to Ginger Pierce & Aaron Jimenez

Dipping into humanistic musings, often swerving into a joke, Margaret Cho’s surefooted conversation discloses a more intimate version of the fiery, raucous, yet thoughtful comedian who is one of America’s first Asian comedians. A pioneer not only for her ethnic singularity but for the racy, cheeky jokes she makes about politics and sexuality, she has named herself a fag hag and a tramp; she jokes about any and every topic banned from family dinners (9/11, heroin, politics, etc.). “The door opens with Margaret. There’s a before Margaret and after Margaret, and I think that’s true with a lot of us,” said Indian-American comedian Hari Kondabolu, in a New York Times article. “I didn’t think it was possible for me to do stand-up comedy until I saw this. This is the reason I do stand-up comedy because Margaret Cho exists. That’s what opened up the world to me.”

But far from giving up the torch, she is as vigorous as ever in her 2025 tour “Live & Livid,” in which she promises to “radiate rage about homophobia, sexism, racism, and the fight to stay alive.” For Margaret Cho, comedy’s ability to surprise the audience is partly what makes the medium suited to radical perspectives. “Real revolution can happen with comedy as a vehicle. Especially in my comedy lately and in my new show, it’s all about resistance, resisting fascism and resisting the current administration, and using ridicule as a means of liberation.”

However, as unrestrained as her jokes can be, Margaret’s jabs are rarely petty or gratuitous. “I get so angry too, and frustrated and I want to attack but at the same time to really be thoughtful about the way that you go about ridiculing,” she says. “Here are the richest people in the world, and the one thing they cannot afford is jokes at their expense. So this is my favorite thing to do, but I want to do it without cheap shots. I want to do this in a thoughtful manner where every joke gets earned and it’s got within it, also, something that the audience is learning about.”

Becoming a better comedian means becoming a more worthy opponent against the targets of her jokes, which are often the current administration, racism and homophobia. It also means being funnier and more entertaining. “I’m not stepping out of what I’ve agreed to society that I would be. I would be an entertainer, and I never want to lose sight of that. I always want to maintain the fact that I’m really laughing at it all still, even though, actually, really horrible things are happening,” she says. “If I don’t laugh, I’ll cry. And laughing and crying at the same time is almost the goal. We want that bittersweet feeling, because the most human truth is within that.”

Bringing about that kind of catharsis for both performer and audience requires, first, vulnerability from the comedian, and the more vulnerable and even incriminatingly honest a comic can be about themselves, the more powerful their message becomes. “I feel strong that I can reveal these kinds of unpleasant things, but at the same time, it gives me a license to talk about other people’s feelings in a way that is more credible,” she explains. She gives an example: “I have this joke about getting peed on. This is very popular— it’s always happened to me, they always want to pee on me— always, always, always. I don’t know what it is, like, I’m not turned on by it, it’s not a kink of mine. But at the same time, I’m also not opposed to it. Doesn’t gross me out, either.

“And so I can talk about that at length, and then kind of bring in the fact that that’s why Melania Trump is so mad. She looks so mad because Donald Trump has urinated on her face so many times. I’m able to kind of reveal this about myself, but at the same time, poke fun of this long held notion that Donald Trump loves to use his urine in a sexual context. It gives it validity.” Her flair for spinning jokes from jokes is almost acrobatic in its leaps of thought, which becomes keenly apparent as she moves deftly into another subject that would render most rubicund and mute.

“I mean, I think it’s so profound that we have a president who cannot, with his own power, urinate and defecate. Like he just doesn’t have control over it. He has to let it go into his diaper and his catheter. I want somebody with more strength than somebody who can’t even control their bowels or their bladder, you know?” But the joke circles back to her: “These are the things that I like to bring up, where also I can barely talk, because I bear very little control over my bowels or bladder. I shit my pants all the time, not out of having faulty piping— I’m just real cocky, and I think I can make it, I think I can hold it.”

Here, she explains, she juxtaposes her own failings with the grander failings of the administration and Trump himself, resulting in a more memorable, powerful, and ultimately funnier joke. Hearing her riff on something as vulnerable as incontinence with unhesitating matter-of-factness, one cannot help but admire how comfortable she seems to be in her own skin, almost too keenly aware to be self-conscious.

For her, vulnerability is a vital part of the craft, and becoming a better comedian requires deeper and braver disclosures about herself. She considers the best comedians the ones who are the most vulnerable and thoughtful, whose introspectiveness is palpable in their comedy. “When you’re really examining your own motives and yourself through your comedy, it becomes altogether more humane, and altogether more funny,” she says. “I think that we’re all sort of pushing towards an ideal. We’d like to be better at what we do, and injecting our own humanity in it.”

At a recent stand-up show, she joked, “I had the first Asian American family TV show 21 years ago. And I fucked it up so badly they had to wait for an entire generation of Asian Americans to be born and grow up with no memory of me whatsoever.” In 1994, Margaret Cho starred in the ABC sitcom All-American Girl, one of the first TV shows that focused on Asian Americans with an Asian cast. As the star of the show, Cho’s stand-up comedy was the basis of the series; however she ended up having little creative control, and under pressure from ABC executives, Cho lost 30 lbs in two weeks and was hospitalized for kidney failure. All-American Girl was cancelled after one season after criticism that it failed to represent the Korean-American community. Being the only series of its kind, it was forced to bear the outsize burden of representing Asian Americans in general, a large and varied group. But despite its short life, the show opened the door for future Asian American series, like Fresh Off the Boat and Beef.

“The solitude, for the longest time, of being the only Asian comedian was really brutal and really frustrating and totally thankless,” Margaret says emphatically. The rewards for her struggles, however delayed, are great— they are the new generations of Asian American comedians indebted to her groundbreaking comedy and series. “They cite me as their sole influence, their sole reason why they do what they do. And that, in itself, is incredibly gratifying,” she says. “I’m still doing comedy shows daily with all of these Asian American comedians that I birthed. It’s a long term, beautiful reward. It is a kind of emotional legacy that I can feel and see and exist within daily.” The comedians Jenny Yang and Atsuko Aktsuka are among those who have expressed profuse gratitude to Margaret Cho. “For me, it’s such a warm and loving experience, to not have to be the only person and to be able to sit back and watch the excellence of people like Ellie Wong, Ronnie Zhang and Sabrina Wu, who are just killing it.”

Amidst the backlash against diversity and DEI, values which had become more popular thanks to artists like Margaret, she wants to clarify that DEI is not a system of handouts. “Backlash to diversity or DEI is really detrimental to the quality of entertainment that we’re going to see,” she says frankly. “The reason DEI is such a popular notion is because people who are underrepresented are going to overproduce. They’re going to produce with excellence not seen elsewhere. It feeds right into what capitalism rewards, which is excellence. When you try to strip DEI out of the equation, you’re just left with mediocrity. It ceases to be a meritocracy. DEI is the reason why there is excellence in the arts; the profound push for more diversity in our programming, in our live entertainment and music and all sorts of the arts, is because we see how it improves the way that we perceive art. It improves the way that we laugh and enjoy things.” The rising popularity of international work in all fields of the arts, from the film Parasite to the series Attack on Titan to K-Pop music, seems testament.

Margaret herself also makes music and plays the guitar as part of a daily practice “just to keep my brain alive,” she says. “It’s also a big part of my social life, because all of my friends also make music, and I like to make music with them.” The death of her longtime friend and inspiration Jill Sobule, a songwriter and a singer, has given her music the new role of working through her grief. “We’re playing all these shows for her now over the summer, which is really beautiful. Coming together with all sorts of different people to play her music has been really healing.”

As a singer and songwriter, she released her newest album Lucky Gift this year, and the title track is a summery pop song about feeling loved unexpectedly. “Like when you feel ugly but you fall in love anyway,” she explains. “That’s such a beautiful statement of love, that it doesn’t really matter if you’re older or you don’t feel so attractive, that we can still feel the giddiness and excitement of other people. It’s the most optimistic thing I think I’ve done as a musician.”

Feeling love in a vulnerable state seems the consummate expression of Margaret Cho’s performances. In the age of the internet, with many of us feeling beholden to picturesque ideals of selfhood, Margaret Cho’s comedy tickles us into remembering that our flawed selves, our vulnerabilities, are the parts of us from which we can draw the deepest confidence, from which we might truly bond with ourselves and others. Our common flaws are what, paradoxically, build our shared ideals of interpersonal harmony and peace— they are our funny, surprising, lucky gifts.

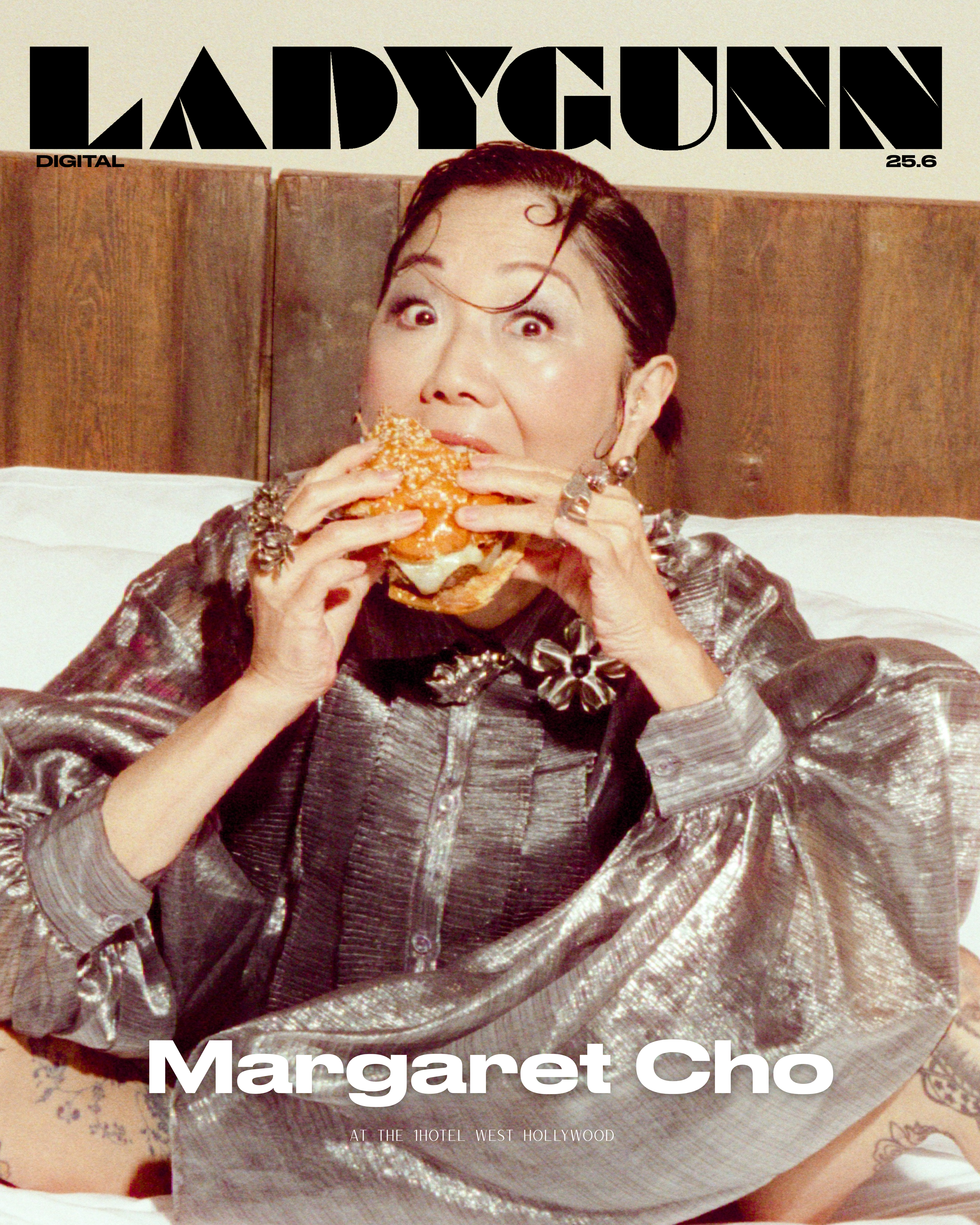

Robe, Gert-Johan Coetzee. Swim Suit, Helene Galwas. Earrings, Chavelli. Eyewear, Burkinabae. Rings, KEANE. Necklace, Alexis Bittar. Gold Chain Necklace and Bracelet, Laruicci. Shoes, Chanel @shoppecroutton.

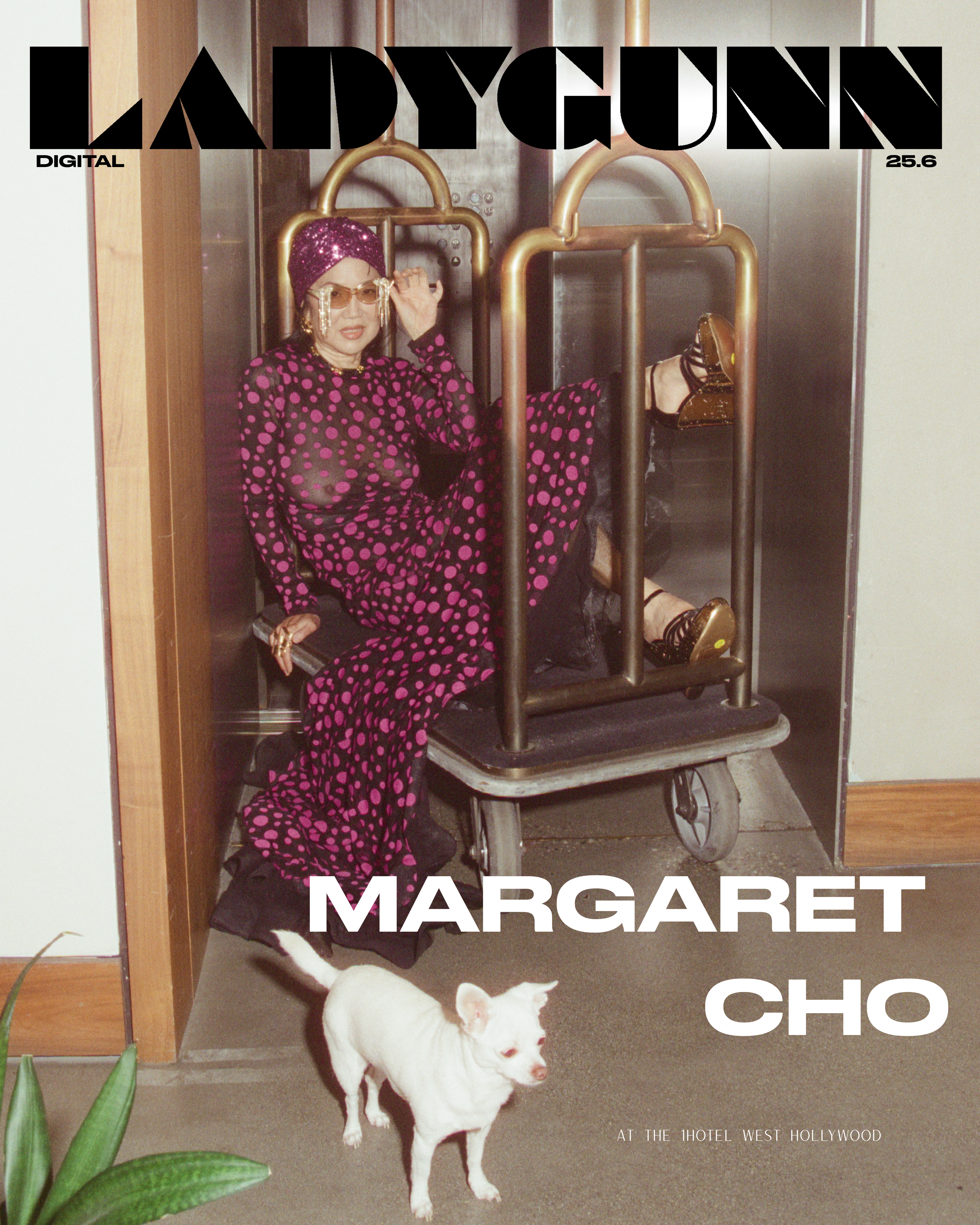

Dress, Gert-Johan Coetzee. Necklace, Alexis Bittar. Eyewear, Burkinabae. Turban, OTT. Shoes, YSL @shoppecroutton.

Bodysuit, OTT. Jewelry, LARUICCI. Rings, Rat Betty. Shoes, Vintage @shoppecroutton.

Dress, AISTĖ HONG. Hat, KABUTÉ. Earrings, Caroline Zimbalist. Eyewear, Betsey Johnson. Gloves, Karolina's Kingdom.